You are here:

- CMP Home >

- Web Exhibits >

- Stereoscopic Images >

- Railroad

- SUBJECT:

- COMPANY:

- GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

Stereoscopic Images of Cleveland in 3-D

Railroad

- This gallery contains 13 slides. Click on the arrows to advance to the next or previous slide.

- Click on the the photo to see the 3-D rendering.

- To view the total effect of the 3-D versions of the images use anaglyph 3-D Glasses (red/cyan).

-

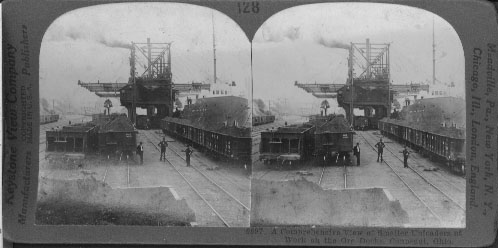

A Comprehensive View of Smaller Unloaders at Work on the Ore Docks, Conneaut, Ohio.

VIEW OF ORE UNLOADERS AT WORK, CONNEAUT, OHIO: On the right is a lake steamer laden with ore from the Lake Superior district. It is at the docks alongside an unloader. This unloader is only a huge steel framework with a number of tracks extending on one side over the dock, and on the other side over the switches. The trucks on these overhead tracks are equipped with buckets which dip the ore out of the hold of the vessel. The bucket is pulled by an engine, up to the truck to which it hooks. This releases the truck, which travels to the other end of its tracks, and there the bucket is lowered and emptied.

The view shows one car on the right being loaded. The truck on the left is dumping its bucket of ore into the freight car. Four series of cars can be loaded here at the same time. The hoist, or steel framework, is 60 feet high and 180 feet long. The bucket is of the type called calm shell. The steel cars into which the ore is dumped are shaped inside like hoppers. That is, their bottoms are sloped. When these cars reach the steel mills, the hopper is opened at the bottom and the ore is dropped into bins below the tracks. Each car can carry 50 tons of ore, and on the return journey will carry 38 tons of coal.

You will observe lying on blocks of wood on the ground, two pairs of steel cables. Each of these cables is slowly moving. When it is necessary to move the car, or the series of cars, to shift them under the buckets, a chain is attached from the cable to the car. When the car had been brought into the proper position the chain is unhooked. -

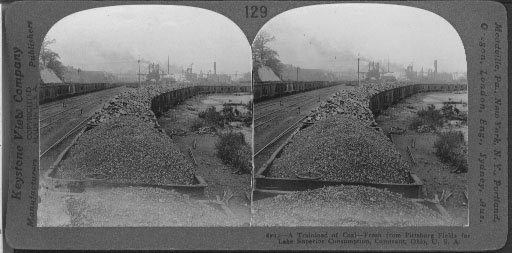

A Trainload of Coal from Pittsburgh Fields for Lake Superior Consumption, Conneaut, Ohio

There is nothing unusual about this scene. On almost any of the great railways in the eastern and middle western sections of our country such trainloads of coal as this can be seen any day. But there is a particular interest connected with this and similar trainloads of coal running from the Pittsburgh district to the Great Lakes. Our greatest iron ore deposit lies at the western end of Lake Superior. In this district, however, there are no coal fields. One of the two things must be done. Either coal must be taken to the ore fields, or the iron must be brought to the coal fields. Coal is needed to heat the iron so that it can be made into steel. When the Lake Superior iron district was first worked, all the ore was carried by huge lake boats to the coal district. But by this method, theses boats had to return empty. This was a great waste. Now the shipping is carried forward both ways. Iron and steel refineries have been built in the Superior District. The vessels that bring iron ore east, carry back heavy cargos of coal to be used in the Superior iron district. This trainload of coal that you see will be put on board one of these ships and unloaded at Duluth or Superior, not far distant from the iron ore area. This make the ports along the southern shore of Lake Erie the natural exchange place of coal and iron. Among these important ports are Buffalo, Erie, Cleveland, Toledo, Ashtabula, Lorain, and Conneaut, the city here shown. Locate each of these cities on your map. Trace a shipment of coal from Conneaut to Duluth. Through what waters does it pass? Lat. 42 N.; Long. 81 W. -

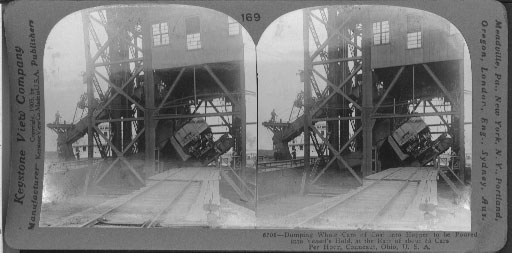

Dumping Whole Cars of Coal into a Hopper to be Poured into Vessel's Hold, Conneaut, Ohio.

This picture shows you how coal is quickly and easily transferred from the railroad cars to the ship's hold. The car which you see on the dock is held by great clamps to the platform. Then the platform, with the car fastened to it, is raised and tipped so that all the coal pours out into a hopper. Other machinery then moves the coal from the hopper to the ship's hold.

The dock in the view is at Conneaut, Ohio. Conneaut is one of the ports along the southern shore of Lake Erie, which has become and exchange place for coal and iron. Our greatest iron ore deposit lies at the western end of Lake Superior. In that district, however, there are no coal fields, and coal must be had to heat the iron ore, and to furnish carbon to mix with it, so that the iron can be made into steel. One of two things must be done. Either the coal must be taken to the iron fields, or the iron must be brought to the coal fields. At first, the iron was taken to the coal fields, and empty boats returned for more ore. Now steel refineries have been built in the Superior district similar to those near the coal fields in the east, so that today the shipping is carried on both ways. The vessels that carry iron east, carry back coal to be used in the Superior district. The coal being loaded at Conneaut will be taken to Duluth or Superior not far from the iron ore area.

Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Ashtabula and Lorain are other ports which have become exchange places for coal and iron. Locate these posts. -

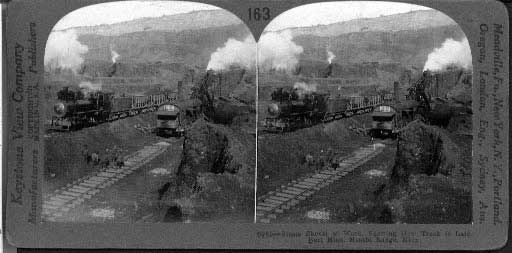

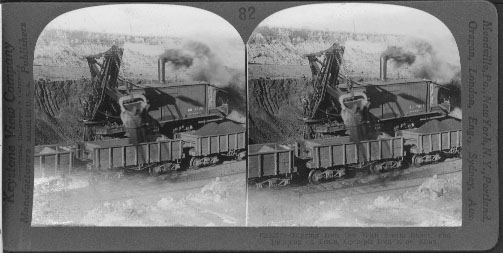

Steam Shovel at Work, Showing How Track is Laid, Burt Mine, Mesabi Range, Minn.

In many was the Mesabi Range is the most wonderful of any mountains in the world. The range is low, most of the mountains being mere hills. But a large part of these hills is made up of free iron ore. The ore, as you see, is scooped up in some places by steam shovels just as gravel is removed from pits.

In most places it is necessary to remove an overlay of several feet of clay. You can see this clay banked in the extreme background. Once the layers of ore are reached, they are removed on different levels. The steam shovel working in the foreground is cutting a trench several yards wide. The ore that it removes is dumped into ore cars that stand on tracks near by. Directly behind the steam shovel another track is being laid. As soon as the ore has been shoveled the full length of the track that is now being made, the ore cars will run on the track in the foreground.

The present Mesabi Range is the foot of an old mountain ridge worn down by glaciers. It is by far the most important iron-ore producing section in the whole world. Annually it produces almost 30,000,000 tons of ore, one-third of the supply of the world. This range, taken with Vermilion and the Cuyuna ranges, all in northern Minnesota, make the United States the leading nation of the world in the iron and steel industry. In recent years, iron smelters have sprung up in this section of Minnesota. The coal and coke needed for fuel are brought by the ore ships on their return trip from the east. But, generally speaking, it is far more profitable to take the iron ore to the coal district than to bring the coal to the iron district. -

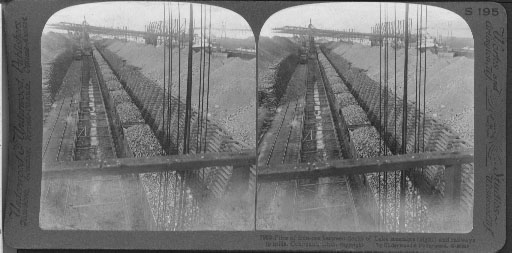

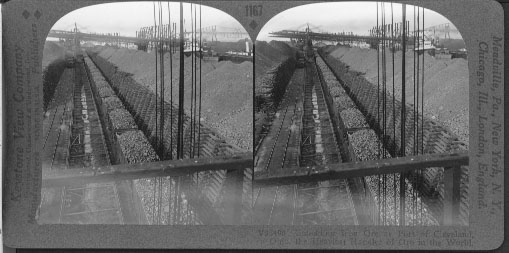

Piles of iron ore between docks of Lake steamers (right) and railways to mills, Conneaut, Ohio.

We are looking north toward Lake Erie. The steamers over there at our right are on Conneaut Creek. Over 4,000,000 tones of iron ore are brought down here every year by Lake Freighters from the richest iron mines on earth, up at the west end of Lake Superior. here are some of the last 4,000,000 now, forming the long line of stock-piles before us on either hand. Those gigantic arms that reach out over the railway track from their anchorage alongside the creek are part of the huge unloading machinery by whose means the ore in all these piles was taken out of the ships' holds and dumped here. Those long steel girders can reach away across the tracks to stock-piles on the west side. The long string of ore-laden cars is on its way to one of the big blast furnaces to b reduced to pig-iron; most of it will go through the huge converters at Youngstown or Pittsburgh and become transformed into steel— perhaps for a railway track in Africa, a bridge across a Himalayan gorge or a new office building in San Francisco. In order to see the underground mining of iron ore, use Stereograph 7954. For gigantic ore docks at the head of Lake Superior, use 7957. For the process of unloading a steamer in 10-ton handfuls, use 7970. The melting of such ore in a blast furnace can be seen with 5520. No 5523 shows the shaping of steel beams in a rolling mill. From Notes of Travel No. 37, copyright by Underwood & Underwood ("Piles of iron ore between docks and railway, Conneaut, O." is written in six languages, including English, French, German and Russian.) -

Lake View Park

No accompanying text. -

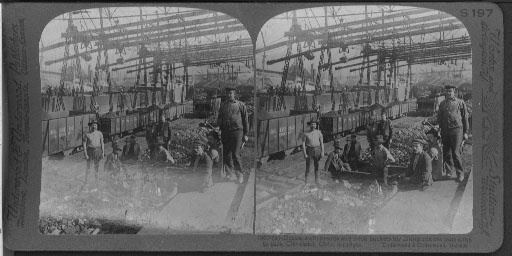

Docks, switchyards and 1-ton buckets for lifting iron ore from ships to cars, Cleveland, Ohio.

We are looking north, i.e., towards Lake Erie, over the great ore docks along the "Old River Bed" canal. Here immense quantities of iron from the Lake Superior mines are transferred to trains and shipped to the famous blast furnaces and steel-mills at Youngstown, Pittsburgh and elsewhere in the Ohio river valley, 100 to 150 miles away at the southeast. The partially crushed ore in the cars here at our feet and that soft, earth-like ore in the cars beyond have both come up from near the head of Lake Superior where the biggest and richest iron mines in the whole world are being worked. The hoisting apparatus overhead makes quick work of unloading a freighter, for those suspended buckets hold a ton apiece. They are run out over a vessel, let down into the hold, filled, drawn up, slid across the intervening space and then lowered for dumping into a car, all in a space of time hardly more than it takes to tell about it. If the supply of empty cars is insufficient, the accumulating surplus forms great stock-piles like those straight ahead, at our right. Still more rapid work can be done with immense "clams" that clutch five or ten tons at once; the gigantic steel derricks of such an unloading plant loom up in the distance at our left. We can watch at short rang the operation of such powerful machines by using Stereographs 7963 or 7970. For the mining of this ore, use 7947 and 7954. For its later manufacture into steel, use 5520-5523. From Notes of Travel No. 37, copyright by Underwood & Underwood ("Docks at Cleveland, O., with apparatus for unloading iron ore" is written in six languages, including English, French, German and Russian.) -

Unloading Iron Ore From Lake Vessels-Old and New Methods, Cleveland, O.

Cleveland is the largest city in the state of Ohio, and it situated on the south shore of Lake Erie at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. It had excellent connection by water with Superior iron regions. It has a lake frontage of about fourteen miles, protected for five and three-quarter miles by a breakwater constructed by the Federal Government. The harbor has unexcelled facilities for handling iron ore. That lake steamer over yonder and the nearer vessel at our left have come down from the western end of Lake Superior, laden with ore for great steel mills at Youngstown, Pittsburg, or Wheeling.

A few years ago the unloading system which we see in operation directly before us was considered splendidly effective. That suspended bucket has been lowered into the vessel's hold and there filled, then drawn along an overhead trolley beam for dumping into the car.

Today the "clam" unloaders are more commonly used. We can see this apparatus looming in the air above that farther pier. By this newer method, five to ten tons of ore can be lifted in one load, and the work can be done much more quickly than by the "pocket" method. -

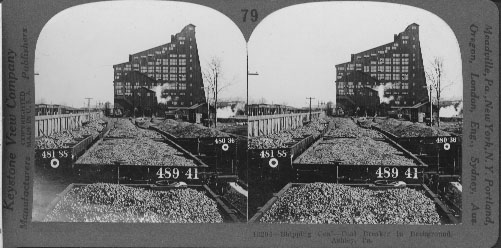

Shipping Coal —Coal Breaker in Background, Ashley, Pa.

CARLOADS OF COAL WITH BEAKER IN THE BACKGROUND, ASHLEY, PA: The big building in the background looks somewhat like a great grain elevator on the plains. It is a coal breaker. It gets its name from the fact that in this building coal is broken into usable sizes. It is necessary to break the coal because it comes from the mine in uneven lumps, some of which are very large.

A breaker is built near the mine shaft so that the small coal cars can be lifted directly from the bottom of the mine to the top of the breaker. Here the large pieces are broken, and as the coal travels downward it is sorted and sifted into its many grades. This is done in the modern breakers by machinery. If you were to ask your coal dealer about the different kinds of coal he would name them according to the size of the lumps. Rice coal is the siftings, the very small pieces. Buckwheat coal is the next size. Then come in order, pea coal, chestnut coal, stove coal, egg coal, and grate coal. There is still a larger variety known as steamboat coal, but this is too large to be burned in an ordinary furnace.

The sorting of these different kinds of coal is done by a system of screens which lie in tiers. Each succeeding screen projects farther out than the one next above it. The finest coal falls into the first row of bunkers, the next in order falls into the next row of bunkers, and so on.

As you see, switches from the railroad are connected with the breaker. The coal falls into car from chutes leading from the breaker. One of these chutes you can see at the left of the breaker building. You will observe that each car is loaded with the same size lumps. These cars carry the fuel that heats our houses, lights our cities, drives our street cars, and runs the machinery of industry.

This tonnage was estimated to be about $1,012,829,000. -

Unidentified Rails.

No accompanying text. -

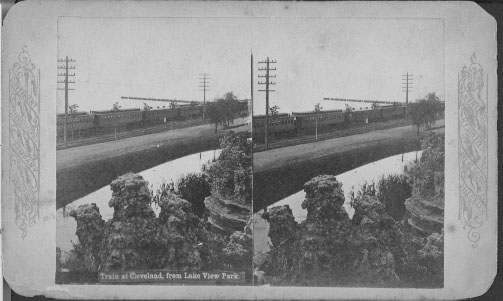

Trains at Cleveland, from Lake View Park

No accompanying text -

Digging Iron Ore With Steam Shovel and Dumping on Train, Open-pit Iron Mine, Minn.

OPEN-PIT IRON MINE, MINNESOTA: Iron is the most useful and most abundant of all metals. It is seldom found in its perfect natural state. It is usually combined with oxygen and other elements and found as a constituent of rocks.

Because of its iron ore, Minnesota holds an important place among the mining states of the Union. In some places the mineral is found here in almost a pure state. This picture is taken near Hibbing, in the northern part of Minnesota. It is in what is called the Lake Superior mining region, probably the largest iron producing section of the world.

Ore was first taken from it in 1884. In less than fifty years the total output of the Lake Superior mines was 192,008,000 long tons. A single mine in Minnesota has produced 1,681,000 long tons of ore in a year. The deposit is near the surface, so that mining can be carried on here on a very large scale. Sometimes the ore is dug out by steam shovels and loaded directly on the cars, as shown in this picture. A single one of these steam shovels can load two hundred cars a day, doing the work which formerly required two hundred men. Most of the ore is shipped by rail to ports on Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, great quantities going to the manufacturing centers of Pennsylvania. -

Unloading Iron Ore at Port of Cleveland, Ohio, the Heaviest handler of Ore in the World.

Iron Ore at the Port of Cleveland: Going westward from downtown Cleveland, we pass over the famous High Level Bridge and Bulkley Boulevard. In going through this part of the city sights such as this are common for many of Cleveland's ore docks and lumber yards are almost hidden on the flat land bordering the Cuyahoga River which empties into Lake Erie. A visit to Cleveland's waterfront is a fascinating adventure. Here we are looking north toward the lake. The steamers we see in the distance have come from the iron county in the vicinity of the western end of Lake Superior, where are located some of the richest iron mines in the world. To the port of Cleveland is brought over 4,000,000 tons of iron ore every year. Those long lines of piles on either side are some of this ore. Those gigantic arms in the distance that reach out over the railway tracks are part of the huge unloading machinery by which means the ore in all these piles has been taken out of the holds of the ships and dumped here. Notice the coal in the long line of freight cars. This coal is to go back to the iron county in the steamer that brought over the ore. These cars will be sent to a coal dock. As soon as the ore boat is unloaded, it will go to the coal dock and be loaded with coal. In turn the ore will be loaded into these cars after they are emptied and thus will reach the iron-manufacturing center where it will be transformed into steel. The steel eventually may reach Africa as a steel rail for a railway track, or Asia as bridge material that will span a Himalayan mountain gorge.